In Mt. Takao, you will see a lot of things decorated with a twisted rice straw rope called a Shimenawa which is regarded as one of the symbols of Shinto, the indigenous religion of Japan.

The role of a Shimenawa in Shinto is similar to that of a Tori-i gate and Komaimu, a pair of stone carved guardian dogs (lions) in that all of them are considered to function as a barrier against evil spirits and a boundary for religious purposes.

Having said that, I suspect that both a Tori-i gate and a pair of Komainu may be relative newcomers in the long history of Shinto and that they may have been introduced much later than a Shimenawa under the influence of the fusion of Buddhism and Shinto.

According to one theory, the concept of a Shimenawa comes from the Japanese mythology.

That is, in the Japanese mythology, there is an episode of the hiding of the Sun Goddess in the Heavenly Rock Cave.

The Sun Goddess is called Amaterasu, literally, shining in the sky, and regarded as the ancestral goddess of the Japanese imperial family.

Obviously, this episode suggests the occurrence of solar eclipse.

The solar eclipse is the phenomenon that the Moon hides the Sun in the daytime.

In this episode, when the Sun Goddess reappeared outside the Heavenly Rock Cave, other gods created a barrier by spreading a Shimenawa all over the Heavenly Rock Cave so that the Sun Goddess should never be able to hide herself in there again.

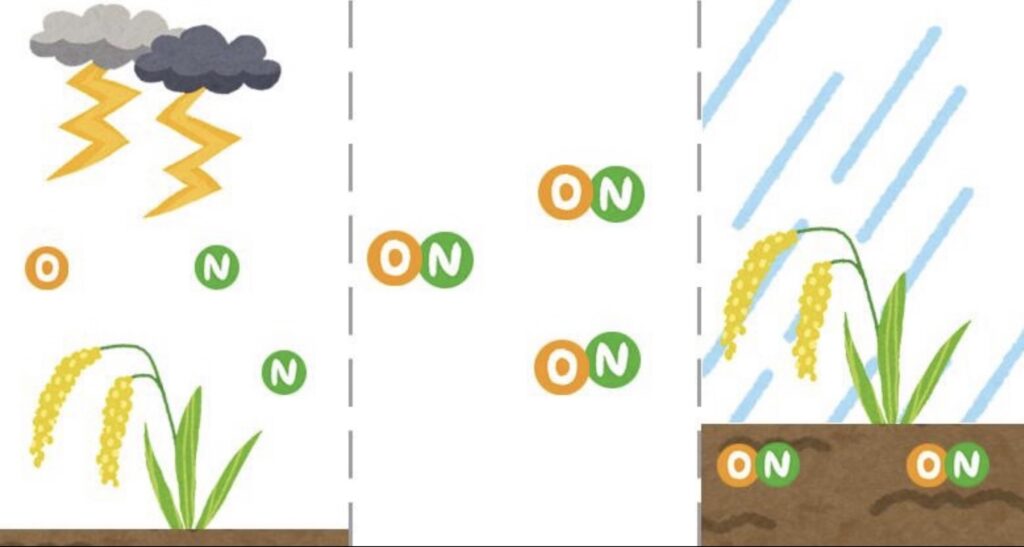

According to another theory, a Shimenawa represents thunderclouds, lightning and rain and symbolizes good harvest.

In this context, a rice straw rope signifies thunderclouds, the zigzag-shaped paper hanging from the rope called shide implies flashes of lightning, and the strands of rice straw hanging from the rope called shimenoko represent rain.

As you may know, rice cultivation had long been the main industry in Japan and even today, Japan’s agriculture centers around the production of rice.

The Japanese name for lightning is inazuma.

Ina means rice and zuma means partner in Japanese.

So, inazuma literally means the partner (husband or wife) of rice.

It’s because lightning is the natural phenomenon that can convert nitrogen in the air into fertilizer that improves growth and productiveness of rice.

That is, the powerful bursts of electrical energy from lightning ionize the air and produce nitrogen oxides which will eventually be transformed into a chemical compound called nitrate by further chemical reaction in the air.

These nitrates are powerful natural fertilizer.

Raindrops carry the nitrates to the ground in a soluble form that plants can absorb.

Thus, the theory that a Shimenawa, which represents thunderclouds, lightning and rain, symbolizes good harvest, is scientifically correct and proven.

Another theory is that a rice straw rope of a Shimenawa is shaped to depict the act of mating of snakes having very strong vitality and shedding their skin to grow as a symbol of fertility and rebirth.

It’s worth checking what is the act of mating of snakes like by viewing the relevant YouTube videos and otherwise although it may be a little bit horrible thing to see for many of the people.

You would be surprised to know that the shape of a Shimenawa and the act of mating of snakes are so similar to each other.

This theory arguably comes from the tradition before the rice cultivation was introduced to Japan when Japanese people lived on hunting and gathering and a Shimenawa is considered to have been made of hemp rope in those days.

Although a Shimenawa is generally considered, along with a Tori-i gate and a pair of Komainu, one of the symbols of Shinto, you can find all of them in Mt. Takao as mentioned in the post titled History of Mt. Takao as a sacred mountain.

Actually, this is also the case with even Mt. Koya in Wakayama prefecture that is primarily known as the world headquarters of the Koyasan (Mt. Koya) Shingen sect of Buddhism.

As you may know, Mt. Koya forms a part of the Sacred Sites and Pilgrimage Routes in the Kii Mountain Range UNESCO World Heritage Site (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1142/).

In Mt. Koya the mausoleum of Kobo Daishi (literally, the Great Priest Kobo) or Kukai who is the founder of Shingon sect of Buddhism and the main gate of Kogobuji-ji Temple are both decorated with a Shimenawa.

You will also see a Tori-i gate installed in front of many of the mausoleums of famous warlords in Mt. Koya.

In Mt. Koya, there is also a Shinto shine called Sanno-in dedicated to the two (2) mountain gods as guardian deities of Mt. Koya where you can see a Shimenawa, a Tori-i gate and a pair of Komainu.

It should be noted that Sanno-in was established by Kukai as the guardian shrine for Mt. Koya, the Buddhist sanctuary he established.

Thus, over the course of history, Shinto and Buddhism have become so intertwined that it is almost impossible to know where one begins and the other ends.

In Mt. Koya, a Shimenawa is often replaced with a cutout picture called “Kissho Hourai” which was devised by Kukai based on the technique he learned in Ruoyang in Tang China because photosensitive rice doesn’t grow in the Mt. Koya where hours of sunlight are short.

In fact, I found this practice even at my family temple in my home town in Kanagawa prefecture which is one of the branch temples of Koyasan (Mt. Koya) Shingon sect of Buddhism.

As you see, although Yakuo-in Temple is officially considered a Buddhist temple, there are dozens of places to be decorated with a Shimenawa there in Mt. Takao.

They are usually renewed once a year during December to be in time for the New Year.

Accordingly, you should in practice have a better chance to see more places decorated with a Shimenawa in Mt. Takao in the earlier part of the year before heavy rains and strong winds, which may be brought by rainy seasons, typhoons and otherwise, may destroy them.

Although I have repeatedly mentioned that a Shimenawa is generally considered one of the symbols of Shinto, it is known that for some reasons we can see neither a Shimenawa nor a pair of Komainu at Ise Jingu Shrine in Mie prefecture, the holiest of Shinto shrines, dedicated to Amaterasu, the ancestral goddess of the Japanese imperial family.

From her experience, she may not like a Shimenawa which can take away the freedom of action from her.

You can see only Tori-i gates there.

Having said that, if you should walk through Ise City where Ise Jingu Shrine is located, you will see a Shimenawa at the gates of the houses all year around.

As you see, a Shimenawa decorated at a gate of a house in Ise City is twisted from the left from the viewer’s perspective.

I suspect that this tradition is to keep the spirit of the god called Gozu Tenno (Gavagriva in Sanskrit) , literally, Bull-Headed Heavenly King inside their houses all year around (rather than to ward off evil spirits) by arranging a Shimenawa the other way around.

In fact, in the Ise region, there is a legend that a poor man gave food and shelter to Gozu Tenno in the guise of a traveler who was looking for a place to stay and the god, as a reward, provided his family a means to save themselves from an oncoming epidemic like the Covid-19 that eventually claimed the lives of those who had turned him away earlier.

The Chinese characters on the wooden tag on the Shimenawa is to tell that the family who live in that house are off-springs of the poor man who gave food and shelter to Gozu Tenno.

Gozu Tenno is enshrined at Yasaka Shrine in Kyoto (https://www.yasaka-jinja.or.jp/en/) and one of the guardian gods of Buddhism of Indian origin.

Gion Matsuri, the festival of Yasaka Shrine which is one of the most famous festivals in Japan began in 869 as a way to appease Gozu Tenno during an epidemic and is listed as one of the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritages (https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/silk-road-themes/intangible-cultural-heritage/yamahoko-float-ceremony-kyoto-gion-festival).

Having said that, in the course of the fusion of Buddhism and Shinto, Gozu Tenno came to be identified as Susanoo, the brother god of Amaterasu and Susanoo is now officially treated as the enshrined deity of Yasaka Shrine after the Meiji Restoration.

I’m running off the track again, I’m afraid.

As discussed in the post titled Looks like Zendoki is another henpecked husband, at most of the shinto shrines, a Shimenawa, the purpose of which is to ward off evil spirits, is generally twisted from the right from the viewer’s perspective in accordance with the Principle of Left over Right with a notable exception of Izumo Taisha Shrine in Shimane prefecture.

Izumo Taisha Shrine is dedicated to Okuninushi, the ruler of Japan before the ancestors of the Japanese imperial family came to power, symbolizing the Earth as opposed to Amaterasu, the ancestral goddess of the Japanese imperial family, symbolizing the Heaven.

The same arrangement is applied to Omiwa Jinja Shrine in Nara which is also dedicated to Okuninushi, alternatively called Ohmononushi.

To the best of my knowledge, another exception is Oyamazumi Jinja Shrine in Ehime prefecture where a Shimenawa is arranged in the same manner as Izumo Taisha Shrine and Omiwa Jinja Shrine for some unknown reasons.

Aside from this, I am aware that some people insist that Usa Jingu Shrine in Oita prefecture and Yahiko Shrine in Niigata prefecture are also another couple of exceptions.

Having said that, I am not sure if this understanding should be accurate.

In fact, I checked on this point directly with the shrine office staff of Usa Jingu Shrine who explicitly confirmed that the Principle of Left over Right is strictly applicable to their arrangement of a Shimenawa while I have heard nothing about Yahiko Shrine on this issue.

On the other hand, it appears that a Shimenawa at the Tamukeyama Hachiman-gu Shrine, which is one of the branch shrines of Usa Jingu Shrine, is also arranged in the same manner as Izumo Taisha Shrine and Omiwa Jinja Shrine for some reasons.

It is understood (i) that when the Great Buddha of Todai-ji Temple was casted, the deities enshrined at Usa Jingu Shrine were summoned all the way from the present-day Oita prefecture in Kyushu as guardian deities of Todai-ji Temple, (ii) that these deities residing in portable shrines travelled from Kyushu and were brought into the precincts of Todai-ji Temple through Tegai-mon Gate of Todai-ji Temple and (iii) that they were eventually enshrined at Tamukeyama Hachiman-gu Shrine that is currently located next to Todai-ji Temple.

It should be noted that Tegai-mon Gate is the only original structure of Todai-ji Temple that have survived two (2) big fires caused by the civil wars in 1180 and 1567 when all the other major structures of Todai-ji Temple had been destroyed.

Although Tegai-mon Gate is a Buddhist style gate, like the main hall of Yakuo-in Temple and the Main Gate of Kongobuji Temple in Mt. Koya, it is decorated with a Shimenawa.

Interestingly, a Shinenawa at the Tegai-mon Gate also appears to be twisted from the left from the viewer’s perspective for some reasons.

Aside from the discussion on from which direction a Shimenawa is twisted, Izumo Taisha Shrine, Usa Jingu Shrine and Yahiko Shrine, each of which has a very long history from the mythological age of Japan, have something in common about the way for a visitor to make a prayer if not about the way to arrange a Shimenawa.

That is, you are supposed to clap your hands four (4) times when you make a prayer at these three (3) shrines, which is obviously different from the manner at all the other shrines where you are supposed to clap your hands just twice when you make a prayer.

It will be a little too long story if told on this issue in this post.

So, let me discuss that issue in more details on another occasion.