You will see Joshin-mon, literally, the Gate of Purified Heart, on Trail 1 which is the front approach to Yakuo-in Temple in Mt. Takao.

Joshin-mon is a type of Tori-i gate.

As mentioned in the post titled Shimenawa symbolizes good harvest, a Tori-i gate is, along with a Shimenawa, a twisted rice straw rope and Komainu, a pair of stone carved guardian dogs (lions), considered to function as a boundary for religious purposes and a barrier against evil spirits.

Joshin-mon is the current first gate to the sacred area of Yakuo-in Temple after the demolition of the original first gate at the foot of the mountain.

The tablet on the Joshin-mon reads, The mountain is full of a spiritual presence.

Many smaller cards or slips bearing Chinese characters stuck to this gate are called senjafuda, literally, a card for a pilgrimage to a thousand of shrines.

They are worshippers’ name cards left at a shrine or a temple as a memorial of the visit.

You are supposed to bow in front of a Tori-i gate to pay your respects to the deities.

It’s polite not to go through the center of a Tori-i gate as the deities are considered to travel through the center of it.

A Tori-i gate is often decorated with a Shimenawa, another symbol of Shinto.

As you may be aware, many of the Tori-i gates are painted red or vermilion because the color of red or vermilion is believed to have the power of warding off evil spirits.

The color of red or vermilion is also considered to represent sunlight and symbolize good harvest as sunlight is very important for the cultivation of photosensitive rice.

This is especially true of Inari shrines the enshrined deity of which was originally revered as the deity of agriculture while with industrialization the deity of Inari shrines gradually came to be worshipped as the deity of business.

It is said that there are some 30,000 Inari shrines across the country (and more than 40,000 if smaller ones are included) with Fushimi Inari Shrine in Kyoto as its headquarter (https://us.jnto.go.jp/japan101/fushimi-inari-taisha-shrine.html).

It is well known that the deity of Inari shrine has been revered by some of the industrial groups representing Japan such as Mitsui and Mitsubishi.

Tori-i gates are generally classified into two (2) styles – Shinmei style and Myojin style, from which some sixty (60) various derivatives have been developed.

The one you will see at the Musashi Imperial Graveyard is classified as a Shinmei style Tori-i gate which is the simpler form of Tori-i gate characterized by the single straight cross bar.

The other type is called Myojin style Tori-i gate which is a more ornamental form of Tori-i gate characterized by the double cross bars with curvature.

Apparently, Joshin-mon is classified as a Myojin style Tori-i gate.

In fact, it is more specifically called Ryobu Tori-i whose pillars are reinforced on both sides by square or angular posts, which is a sign of the fusion of Shinto and the Shingon sect of Buddhism.

One of the most famous Tori-i gates of this type is the Great Red Tori-i of Itsukushima Shrine in Hiroshima prefecture, which is one of the World Heritage Sites (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/776/).

The Tori-i gate of Hiyoshi Taisha in Shiga prefecture is also classified as a Myojin style Tori-i gate.

Having a temple style roof on top of the Tori-i gate, it is more specifically called Sanno Tori-i which signifies the fusion of Shinto and the Tendai sect of Buddhism.

Even in the center of Tokyo, you can see this type of huge Tori-i gate.

As discussed in the post titled Optional Tour to the Musashi Imperial Graveyard on the way back from Mt. Takao, the origin of a Tori-i gate is unknown.

There are several different theories on the subject, none of which has been universally accepted.

Let me discuss two (2) of them that appear to be more convincing.

According to one theory, a Tori-i gate originated from torana gates installed in front of a stupa in the ancient India.

A torana refers to an ornamented gateway leading to a stupa or temple in Buddhist and Hindu architecture.

According to this theory, a torana was adopted by Kobo Daishi (literally, the Great Priest Kobo) or Kukai (774 – 835) who is the founder of Shingon sect of Buddhism.

It is said that he used it as a boundary to separate the sacred space for ”Goma Fire Ritual”.

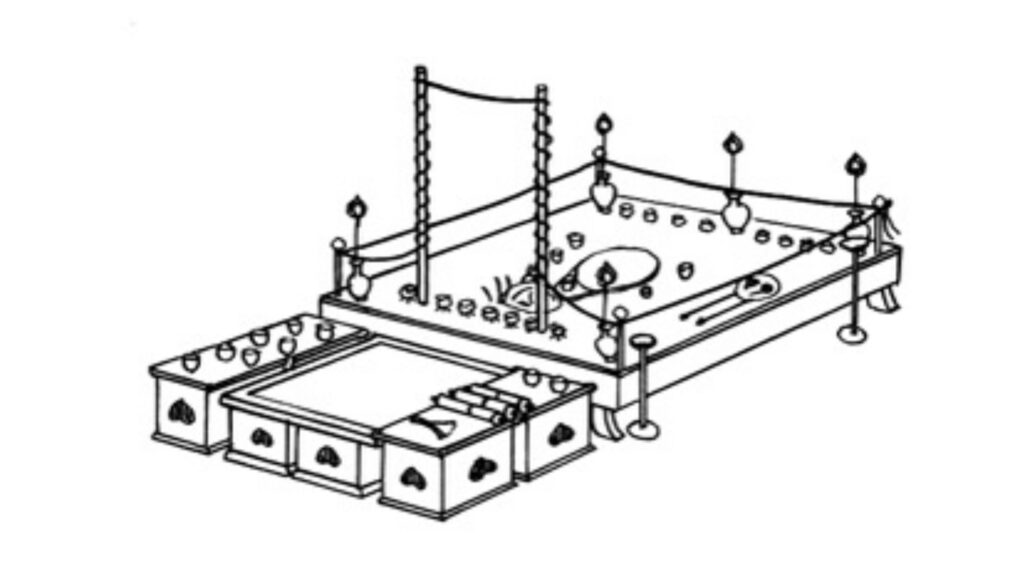

Goma Fire Ritual refers to a Buddhist ritual of burning wooden sticks called goma-gi (homa sticks) at the fire altar called Gomadan for divine blessings.

In the course of fusion of Buddhism and Shinto, Goma Fire Ritual has also come to be conducted at some of the Shinto shrines.

Author: Bachstelze

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/6e/Gomadan_of_Hiwashi-jinja_shrine.JPG

As you see, in front of the fire altar called Gomadan, there is a Tori-i gate like object.

In fact, Goma Fire Ritual is conducted every day at the Gomadan in the main hall of Yakuo-in Temple in Mt. Takao in which you can participate for a minimum fee of JPY3,000 as of today.

In Mt. Takao, Goma Fire Ritual is also conducted on a less frequent basis at the outdoor fire altar called Saito Gomadan at Yuki-en which you can observe free of charge.

As you see, in the case of the outdoor Goma Fire Ritual, a sort of Shimenawa is used as a boundary to separate the sacred space for the ritual.

Goma Fire Ritual is said to have been introduced by Kukai from Tang China while the ritual is said to have originated in India.

The Japanese word Goma is read Homa in Sanskrit, and means to burn.

It signifies that the fire of Buddha’s wisdom is used to completely burn up your worldly sins or desires, the source of sufferings.

Goma Fire Ritual is also said to be closely associated with an ancient Persian religion, Zoroastrianism founded by Zoroaster in which fire is worshipped as god.

I’m afraid that I’m straying from the original topic a little bit again.

Having said that, the foregoing should also be able to explain why we see many Tori-i gates in Mt. Koya in Wakayama prefecture which is primarily known as the world headquarters of the Koyasan (Mt. Koya) Shingen sect of Buddhism established by Kukai.

It is understood that the oldest Tori-i gate in existence in Japan is Motoki Stone Tori-i in Yamagata prefecture.

This oldest Tori-i gate in existence is said to have been constructed in 973 – 976.

So, we can reasonably assume that the concept of Tori-i gate has been existing since some time in the Heian period (from the late 8th century to the late 12th century) which can also support this theory.

The other theory is that a Tori-i gate may be derived from the Japanese mythology like a Shimenawa.

That is, it is again related to an episode of the hiding of the Sun Goddess in the Heavenly Rock Cave.

When Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess, locked herself up in the Heavenly Rock Cave after a quarrel with her brother god Susanoo, the world became dark.

Other gods got together in front of the Heavenly Rock Cave and had a great festival to get and lure the Sun Goddess out of it again.

Firtstly, other gods gathered chickens called Tokoyo no naganakidori (literally, a long-singing chicken of eternal world) that tell the end of the night and made them crow each other to encourage the sunrise (i.e. the reappearance of the Sun Goddess).

So, this theory is that the origin of Tori-i gate should be a bird perch for Tokoyo no naganakidori.

As mentioned in the post titled Optional Tour to the Musashi Imperial Graveyard on the way back from Mt. Takao, Tori literally means bird and i literally means reside in Japanese.

Having said that, in the above painting depicting the legend of Heavenly Rock Cave, we cannot find any bird perch like object.

Looks like Tokoyo no naganakidori is just standing next to the goddess, Ame-no-Uzume who successfully lured out the Sun Goddess from the Heavenly Rock Cave, saving the world from eternal darkness.

Actually, Ame-no-Uzume, who performed a comical erotic dance making other gods burst into laughter in the boisterous merrymaking, is regarded as the goddess of performance arts in Japan.

I am personally for the theory that a Tori-i gate as a symbol of Shinto originated from Buddhism in the ancient India.

As discussed in the post titled Shimenawa symbolizes good harvest, an episode of the hiding of the Sun Goddess in the Heavenly Rock Cave obviously suggests the occurrence of solar eclipse.

Kojiki (the Record of Ancient Matters), the oldest written history book of Japan compiled in the early 8th century, does include this episode.

We could reasonably assume that the author of Kojiki came up with this plausible story based on the then cultural background.

Having said that, to the best of my knowledge there is no specific reference to a bird perch for Tokoyo no naganakidori or Tori-i gate in the episode of the Heavenly Rock Cave of this oldest history book itself.

According to the recent Religious Statistics Survey conducted by the Religious Affairs Division of the Agency for Cultural Affairs, the number of Shinto shines is estimated to be more than 80,000 across the country.

If smaller shrines should be included, this number could be 200,000 – 300,000.

All these Shinto shrines may not necessarily be equipped with Tori-i gates while even at Yakuo-in Temple in Mt. Takao that does not appear to be classified as a Shinto shrine for the purpose of this survey we can still find multiple Tori-i gates.

It is no wonder that our daily lives are full of landscapes with Tori-i gates.