Aside from a Tori-i gate and a Shimenawa, a pair of stone carved guardian dogs (lions) called Komainu is “generally” regarded as a symbol of Shinto, the indigenous religion of Japan.

A pair of Komainu, however, are often seen around some of the Buddhist temple gates as well.

I believe that it is because the concept of Komainu arguably comes from Buddhism.

Koma (Goryeo) in Japanese is the name of the united nation of the Korean peninsular established in the 10th century and inu in Japanese means a dog.

So, Komainu literally means a Korean dog, effectively, a foreign dog or non-Japanese dog.

A pair of Komainu are considered to function as a boundary for religious purposes and a barrier against evil spirits.

So, their role is very similar to those of a Tori-i gate and a Shimenawa.

We could say that a Tori-i gate, a Shimenawa and a pair of Komainu constitute a three-piece suite of an entrance to a Shinto shrine.

Having said that, as discussed in the post titled Shimenawa symbolizes good harvest, it is well known that for some reasons we don’t see either a Shimenawa or a pair of Komainu at Ise Jingu Shrine in Mie prefecture, the holiest of the Shinto shrines, dedicated to Amaterasu, the ancestral goddess of the Japanese imperial family.

It is understood that at Ise JIngu Shrine, a sacred evergreen tree called Sakaki is used as a boundary for the religious purposes along with Tori-i gate.

It is also known that at Ise Jingu Shrine no Omikuji is available.

Omikuji refer to fortunes written on slips of paper.

People buy them at Shinto shrines and, occasionally, Buddhist temples, and tie them onto the branches of nearby trees or such other places as designated by Shinto shrines or Buddhist temples in hopes that a good fortune will come true or that a bad fortune will be kept away.

Generally speaking, there are five kinds of fortune: great fortune, good fortune, good fortune in the future, bad fortune, and great misfortune.

According to one survey, most of the Shinto shrines or Buddhist temples take a customer friendly approach by decreasing the number of fortune telling papers bearing bad fortune and great misfortune down to some 5% of all the fortune telling papers.

I guess that Ise Jingu Shrine, as the holiest Shinto shrine, has been trying to distinguish itself from other less prestigious Shinto shrines by refraining from jumping at the latest fashion including anything that may come from the fusion of Shinto and Buddhism as much as possible.

In Mt. Takao, a sacred mountain of Shugendo that is the product of the fusion of Buddhism and Shinto, you can see the above mentioned three-piece suite as well as Omikuji, fortune telling papers, etc.

Yakuo-in Temple is quite flexible, isn’t it?

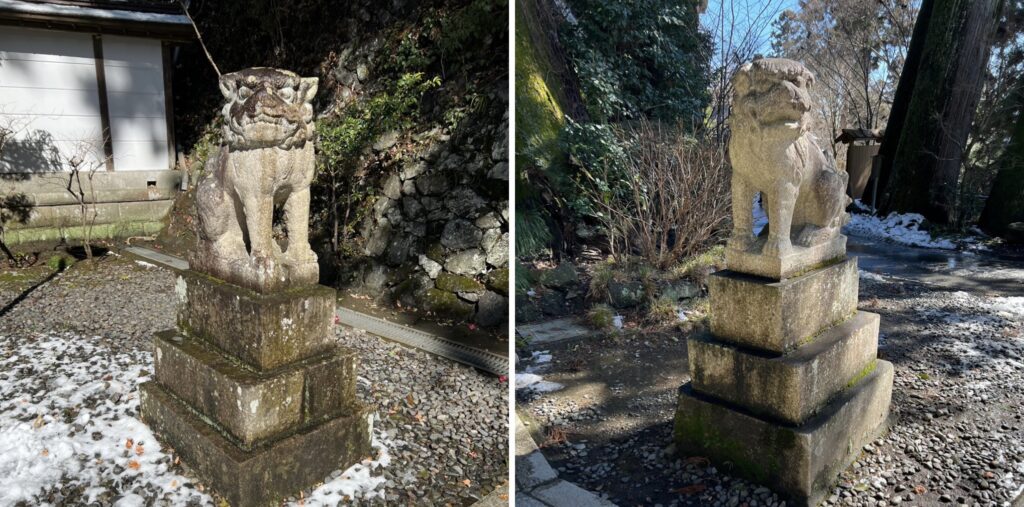

Going back to the topic of Komainu, there are three (3) pairs of Komainu in the precincts of Yakuo-in Temple in Mt. Takao.

All of them in Mt. Takao are “Ah-Un” statues.

That is, a Komainu on the right from the viewers’ perspective opens its mouth and is considered a male Komainu while a Komainu on the left from the viewers’ closes its mouth and is considered a female Komainu.

It is understood, however, that when Komainu was introduced to Japan in the Asuka period (from the late 6th century to the early 8th century) the common arrangement was that two (2) identical statues stand side by side and that the Ah-Un style was not applied to a pair of Komainu until the Heian period (from the late 8th century to the late 12th century) .

Judging from their appearance, it might be more appropriate to call them guardian lions.

One theory is that the origin of Komainu is the pedestal of statues of Shakyamuni Buddha decorated with a pair of guardian lions that was created by people in the Gandhara region, the present-day Peshawar in Pakistan under the influence of Greek sculpture.

In fact, even in Japan, we can find the statues of Shakyamuni Buddha commonly attended by the statue of Monju Bosatsu (Manjusri Bodhisattva in Sanskrit) riding a lion and the statue of Fugen Bosatsu (Samantabhadra Bodhisattva in Sanskrit) riding an elephant.

It can reasonably be assumed that when these statues were introduced through China and Korea to Japan in the 7th century, Japanese people had never seen lions by that time.

So, Japanese people in those days may have thought that this ferocious looking creature must be a Korean dog or a dog that breeds and inhabits elsewhere outside Japan.

Probably, a pair of Komainu came to be installed at Shinto shrines as well over the course of time under the influence of the fusion of Shinto and Buddhism.

Personally, I believe that among a three-piece suite of an entrance to a Shinto shrine, at least two (2) of them (i.e. a pair of Komainu and a Tori-i gate) come from Buddhism.

It is understood that in the early days a pair of Komainu were commonly installed indoors and the statues were mostly made of wood taking advantage of abundant forest resources in Japan.

In the Heian period, the appearance of a pair of Komainu became different from each other.

The statue on the left with a horn on head from the viewers’ perspective was specifically called Komainu while the statue on the right from the viewers’ perspective was called Shishi or Karajishi (literally, a Chinese shishi or foreign shishi) to distinguish it from a Japanese shishi (i.e., Kano-shishi (deer) or Ino-shishi (wild boar)).

Looks like it was around the end of Heian period or the early Kamakura period (the late 12 century) that a pair of stone carved Komainu started becoming common in the situation that they came to be installed outdoors.

The oldest pair of stone carved Komainu in existence is said to be the one installed at the Great South Gate of Todai-ji Temple.

They are said to have been created by a group of stonemasons from Song China who were invited for the reconstruction of the Great Buddha Hall that had been destroyed in the civil war in 1181.

Although the application of Ah-Un style to a pair of Komainu had already become very common by that time, this pair of stone carved Komainu is not in the form of Ah-Un statues.

Probably it is because they were created by non-Japanese stonemasons.

In fact, it is known that some other pairs of stone carved Komainu including the one at Kiyomizu Temple in Kyoto are modeled on the pair at the Great South Gate of Todai-ji Temple.

As you see, a pair of Komainu in front of the Nio-mon, literally, the Gate of Two Heavenly Kings in the grounds of Kiyomizu Temple in Kyoto both open their mouths.

In the Edo period (from the early 17th century to the late 19th century) a Komainu with a precious stone on its head became popular.

One of the pairs of Komainu in the precincts of Yakuo-in Temple in Mt. Takao has this unique feature.

As you see, the male Komainu on the right from the viewers’ perspective open his mouth juggling a precious stone with his head like a professional soccer player while the female Komainu on the left from the viewers’ perspective closes her mouth having two (2) horns, which may indicate that she wears the pants.

At my place, we have a Komainu-like pair of statues called Shisa that are Okinawan guardian lions and said to have been introduced from China in the 13th – 14th centuries.

They appear to be active in the ordinary or mundane world and often placed on rooftops or gates of houses in Okinawa.

Obviously, they are a sort of cousins of Komainu with Ah-Un style.

In China, you will also see a lot of statues of guardian lions at gates of a lot of buildings.

So, like Shisa they are also active in the ordinary and mundane world.

Looks like a pair of Chinese style stone carved lions both open their mouths like a pair of Komainu installed at the Great South Gate of Todai-ji Temple that are said to have been created by stonemason from Song China.

So, we could say that Ah-Un style stone carved guardian dogs (lions) are unique to Japan.

Incidentally, when we think of lions, most of us may think of Africa.

But, I hear that in India there still exists one tiny community of wild Asian lions, a remnant of a once much larger population, which could suggest that the concept of Komainu originated in the ancient India.

Having said that, according to one theory, the origin of Komainu is a Sphinx found in Persian, Egyptian, Greek cultures, etc.

Seeing that Buddhist statues started being created in the ancient India under the influence of Greek sculpture, this theory is also convincing.

It’s a very interesting exercise to trace back the origin of Komainu beyond time and space, isn’t it?

Instead of a pair of Komainu, at some of the Japanese Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples, you can find some other guardian animals such as wild boars (Komainoshishi), monkeys (Komazaru), rabbits (Komausagi), mice (Komanezumi), etc., which seem to be a sort of derivatives developed from Komainu at a later stage.

It is well known that at Inari shrines I mentioned in the post titled The origin of a Tori-i gate as another symbol of Shinto instead of a Komainu a pair of fox statues play the similar role.

In fact, you should be able to find many of the fox statues in front of the Inari shrine in the precincts of Yakuo-in Temple in Mt. Takao as well.

On your next visit to Japan, if you should have any opportunities to visit Japanese Shinto shrines and/or Buddhist temples, you might enjoy variations of Komainu and their siblings or cousins.